Port History

For over 100 years, the Port of Coos Bay has facilitated the economic growth and development in the Southwest Oregon region and the state.

The First Vessel

In 1836 the first vessel to enter Coos Bay was a British sloop-of-war. The Army transport schooner Captain Lincoln was stranded with a load of supplies in 1851 at what they called Camp Castaway on the North Spit, and the rest is history. The first settlements of whites was at Empire in 1853.

Early Years

The first federal project was authorized in 1878 from Fossil Point westward. Considerable work was accomplished in the early 1880’s, but was discontinued when it became apparent that it was not working as intended. North Jetty was started in 1891, and fully completed 10 years later. The Fossil Point Project is now referred to as the submerged jetty.

Both sailing vessels and steamboats engaged in the early coastal shipping traffic which called at Coos Bay. The steamers carried passengers and freight, and sometimes bulk cargoes, while sailing ships carried mostly bulk cargoes of lumber and coal. As a rule, the bulk cargo carriers were laden with paying cargo only on the outbound leg of their journey. There was practically no incoming bulk cargo into Coos Bay, and as a consequence, the ships brought in quantities of stone as ballast.

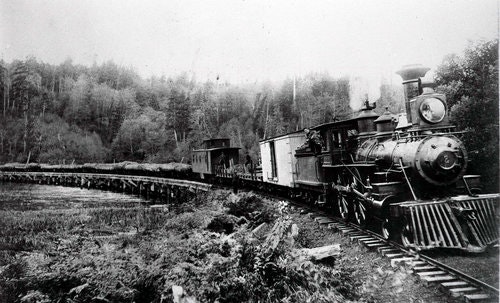

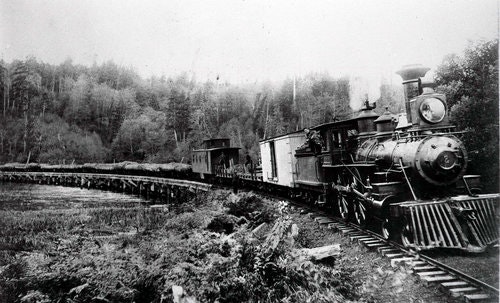

Early Railroad

Railroads had been part of the facilities of the Port of Coos Bay since the 1890's, but until 1916, the Port had no rail connection with other parts of the state. In 1898, construction started on a rail line between Coos Bay and Coquille. In 1893, the line reached Myrtle Point, but no further progress was ever made in building the rail line on to Roseburg. Before completion of this line, the agricultural products of the fertile Coquille Valley had been shipped out across the treacherous Coquille River bar at Bandon. As soon as the railroad reached Coquille, those products began to be diverted through Coos Bay, and they constituted an important part of the exports from Coos Bay. Despite the failure to reach the main line in the interior, the Coos Bay, Roseburg, and Eastern was an important part of the transportation system which led to the Port.

Port

Action to organize a formal port governing body, with taxing authority, originated in 1908. Early in 1909, enabling legislation was enacted by the Oregon Legislature and signed into law by the Governor. Previously, the Port of Portland had been organized in Oregon under special legislation, which was subsequently found to be unconstitutional. The act of 1909 cleared the issue, and allowed all de facto ports in the state to organize as municipal bodies. Immediately, Coos Bay commercial interests, who had been instrumental in having the law passed, set out to establish the Port of Coos Bay. The land area upon which taxes could be levied was defined as the area which drained into the bay.

The question of formation of the Port of Coos Bay was introduced to Northern Coos County voters in April, 1909, and the measure passed by a 5-1 margin. A test case to establish the constitutionality of the new port law was instituted in Oregon courts at once. That case required more than three years to be decided, and while it was being heard and appealed in successive courts, the Port of Coos Bay continued to operate, but without a tax levy.

Charleston Marina

Meanwhile in the early 1900s, the unincorporated community of Charleston was primarily comprised of small rural homesteads, with a few business ventures scattered amongst the hills and valleys surrounding both sides of the middle and upper sections of South Slough, but most were clustered toward the north end of the waterway.

Coos Bay Rail Line

The Southern Pacific Railroad gained control of the Coos Bay, Roseburg & Eastern line in 1906, and began at once to search for routes other than that through the difficult Coquille Valley to Coos Bay. After an expensive false start on an Umpqua Valley route, the Southern Pacific Railroad began construction in 1909 on the Eugene-Siuslaw Valley route.

Port

In 1912, the body of 1909 was disbanded, the Port of Coos Bay was thrown into the hands of a receiver, and the Port governing body reorganized under a revised charter. The reorganized Port soon sold a $300,000 bond issue for the improvement of the harbor. That money was intended for internal dredging to increase the interior channel depths to 25 feet and to dredge wide turning basins at selected points inside the harbor.

Charleston Marina

In 1915, the U.S. Coast Guard built a life-saving boathouse near the ocean entrance to Coos Bay, not far from their lookout station on Coos Head. Shortly after, in 1917, the first store in Charleston was up and running and a village began to grow.

Coos Bay Rail Line

The Corps of Engineers predicted that rail service connecting Coos Bay with the main railroads would have only a minor effect on shipping through the Port. However, after the line was finally completed in 1916, there was an immediate and drastic effect on the waterborne passenger traffic of the Port. That business dropped from a high of almost 22,000 passengers carried by the ships serving the Port in 1914, to a low of 650 in 1918.

Port

Although the railroad carried carloads of wood specialties from the veneer mills, the sawed lumber which comprised the bulk of the Port's traffic went out across the bar in ships. During the 1920's that tonnage averaged over 520,000 tons a year, far more than any previous year other than 1914, which was an exceptional year when over 500,000 tons passed through the Port. Yet the channel was only marginally better in 1930 than in 1919. The controlling depth of 18 feet in 1920 had been increased only to 20 feet by 1930. Of the 391 vessel which left the harbor in 1929, only 25 drew over 20 feet on departure, and none drew over 21 feet. The export of large tonnages from the Port during the decade was the result not of the improvements to the harbor, but of strong demand for the products of the harbor and of the use of expedients which included partial loading, taking advantage of high tides, and seasonal shipping.

Charleston Marina

During the early 1920s marine science students from the University of Oregon in Eugene made regular field trips to the Charleston area, and a small campus was established in 1928-29 on the Coos Head Military Reservation property along what was then the Charleston bayfront; now the approximate location of Boat Basin Drive. In 1931 the property that is the current Oregon Institute of Marine Biology (OIMB) was deeded to the University by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. (oimb.uoregon.edu). The 1920s (1924-28) also saw the construction of the south jetty of Coos Bay, which resulted in more stores, a tavern and a dance hall in Charleston.

Port

The River and Harbor Act of 1930 provided for moving the channel at Pigeon Point to the west and for deepening the channel to 24 feet through the reef. Channel depth elsewhere in the bay was to be 22 feet, as previously approved, and channel width was to be 300 feet through Pigeon Point and opposite the cities of North Bend and Marshfield. Channel width for most of the bay was to remain at 200 feet, with a reduction to 150 feet in Isthmus Slough. The project to deepen the channel through Pigeon Point was completed on October 2, 1931. The correction of the channel there went far toward making Coos Bay a more modern harbor--capable of serving many of the larger world cargo ships of the day.

Although the output of the Coos Bay mills had been stable during the 1920's, individual mills had not operated steadily in that period. The cargo mills had operated only because they could dump their output on the California market at below market price, using shallow-draft coastal lumber carriers to deliver their product. Using tonnage through the Port of Coos Bay as a measure of the economy, the decline started in 1931, reached a low point in 1932, and made a slow recovery through 1934. Tonnage increased remarkably in 1935, and continued to grow. The Port was aided in that recovery by the major project of deepening the harbor which was completed after 1935.

Those interested in improving the Port had always pressed the government for channel depths greater than the Corps of Engineers thought necessary. When the Depression struck, it became apparent that it was time to conduct a renewed campaign for a deeper and wider internal channel as a public works project. After some years of lobbying by Port interests, Congress passed the River and Harbor Act of 1935, which included provisions for a 24-foot channel from Pigeon Point to the mouth of Isthmus Slough, with a general width of 250 feet, except through Pigeon Point and at Marshfield and North Bend, where the width was to be 300 feet. A width of 450 feet was authorized in the vicinity of the railroad bridge at the north end of the bay, and a turning basin 600 feet wide by 1,000 feet long was planned for the area near the mouth of Coalbank Slough. Work was started in 1936, and was completed in 1937. More careful records were kept after the completion of this project, and as the years progressed, the trend toward deeper-draft vessels became apparent in the late 1930's and early 1940's.

Roads and Bridges

Meanwhile, modern road and bridge building was taking place in the area which was a tributary to the Port. As the timber near the bay was cut, the logging moved further away into the rugged terrain of the Coast Range. In the 1930's, public roads and highways superseded the use of privately funded railroads as a means of transporting timber out of the woods. The McCullough Bridge was named for the Oregon State Highway Department bridge engineer C.B. McCullough, and greatly facilitated transportation of logs and sawed lumber to the Port, and eliminated a long ferry trip across the bay for thousands of automobile passengers each year. Completion of the McCullough Bridge and others in southwestern Oregon in the 1930's did much to relieve the geographic isolation of the area and to improve transportation to the Port.

Infrastructure Improvements

Major maintenance work on the jetties was conducted in late 1930 and early 1940. Restoration of the North Jetty took place between 1938 and 1940. A railroad spur was extended from the main line on the north side of the bay to the jetty site on the North Spit, and rock was brought in from quarries on the Umpqua River. The South Jetty was also completely repaired during the years 1940 and 1942. The channel of the inner arm of the bay was maintained, as in the past by contract dredges, although the Port of Coos Bay dredge did not perform that duty after the early 1930's. The beginning of the Second World War found the Port of Coos Bay in excellent condition because of the improvements and maintenance which had been conducted during the 1930's.

Charleston Marina

There was continuing development through the 1930s in Charleston as well with the construction of the original Charleston-South Slough Bridge in 1934, linking the Barview area with Charleston proper. With this new roadway connection to the regional highway system several fish processing plants were built on both sides of the new bridge, and many local fishing boats were moored at the docks owned by the plants or at a fish processing plant at Empire. The Oregon Department of Transportation replaced this bridge in 1991. The late ‘30s also marked the start of oyster aquaculture in Coos Bay with the first commercial oyster beds in Joe Ney Slough in 1937. As more commercial fishing infrastructure was added, Charleston emerged as a lively and often rowdy coastal fishing village.

Port

The effect of the Second World War on the Port of Coos Bay was much the same as that of the First. Shipping through the Port was sharply reduced in the years 1943 through 1946, and tonnages fell to near the low levels of 1917 and 1921. The big cargo mills still operated, but not steadily, and much of their output was carried to market by rail. Despite the general requirement that vessels be constructed of welded steel plates, Coos Bay was still engaged in the building of wooden hulls, and four wooden minesweepers, developed especially for the clearing of magnetic mines, were built for the U.S. Navy. The war with Japan deprived Coos Bay of an important market. Coos Bay shipped nearly 50 percent of its freight to foreign ports in the mid-1930's, and most of that tonnage went to Japan. Before America's entry into the war, Coos Bay had participated in the scrape metal trade with Japan. When the war came, not only did trade with Japan end, but other markets were also shut off because of a lack of shipping. Nevertheless, shortly after the war, the Coos Bay cargo mills were sawing lumber at a rate which equaled then exceeded that of the record years between the wars.

Those interested in improving the Port had not allowed the war to blunt their determination to obtain better and deeper harbor facilities. Congress authorized a new survey of the harbor in March 1945, followed by the July 1946 River and Harbor Act, which allowed the Corps of Engineers to develop and maintain a depth of 40 feet over the bar, but required that the depth be gradually reduced to 30 feet inside the jetties. In addition, the channel was widened to 300 feet throughout, with two 600-foot wide turning basins, 2,000 feet long were to be established on the outer arm of the bay. The project was completed in January, 1951, however, project width was not reached until 1952.

Tonnage Improvements

In 1946, shipments from Coos Bay were less than 400,000 tons, but more than half of that went to the foreign market--a forecast of future trends. In 1947, tonnage increased to near the bestof the pre-war times. However, not until 1949 did cargo shipped from Coos Bay exceed that of 1923, and in 1950, the Port set a new record of over 900,000 tons a year. Reconstruction in Europe and the post-war building boom, combined with the demands for lumber created by the Korean Conflict, resulted in a market for the products of Coos Bay which had never previously existed.

Charleston Marina

One of the most popular attractions in the Charleston area is Shore Acres State Park. The original parcel of the Simpson family estate was acquired by the State of Oregon in 1942, with later property additions between 1956 and 1980. The park is a world-renowned botanical garden attracting more than 200,000 visitors per year. (www.shoreacres.net)

During the winter of 1945, a series of severe storms did significant damage along the bayfront around what is now known as Charleston harbor. The port commission, at the urging of Charleston residents, business owners, the Coast Guard, fish plant operators, fishermen and others contacted the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to discuss the construction of breakwaters or jetties to protect the village and to help with ongoing development of the northern section of South Slough. In addition to the breakwaters, the community wanted a mooring basin, tidal control dikes and access channels. OIMB personnel regularly described the loss of bayfront property of as much as 20 to 40 feet during winter storm events.

The River and Harbor Act of 1946 authorized deepening of Coos Bay’s main navigation channel, and resulted in the construction of breakwaters and access channels at Charleston. It was dredged material removed from the channels that led to the creation of the upland area now encompassing the inner boat basin, the current U.S. Coast Guard Charleston Lifeboat Station and other developments to the east of the present day OIMB.

Charleston Marina

Work on the navigation system continued through 1956. When the project was complete, channels in the Charleston area were authorized at -10 feet MLLW (Mean Lower Low Water). Today channel depths in the Charleston harbor area are -18 feet MLLW, and channels extend from the main Coos Bay navigation channel to the Charleston-South Slough Bridge. What is today the Charleston Marina outer basin was developed in 1956, and later expanded by excavating the upland to create the inner boat basin in 1966.

Charleston Marina

Work on the navigation system continued through 1956. When the project was complete, channels in the Charleston area were authorized at -10 feet MLLW (Mean Lower Low Water). Today channel depths in the Charleston harbor area are -18 feet MLLW, and channels extend from the main Coos Bay navigation channel to the Charleston-South Slough Bridge. What is today the Charleston Marina outer basin was developed in 1956, and later expanded by excavating the upland to create the inner boat basin in 1966.

Port

In 1987, the Oregon Legislature passed SB 962, which created only the second State Port in Oregon. This legislation was overwhelmingly approved by 73 percent of the voters in the Port District. This legislation not only created a closer bond with State government, it allowed the Governor to appoint the Board of Commissioners, which was expanded from a fie-member Board to seven members (two from outside the Port District) for a four-year period. A later ballot measure to retain the two out-of-district Commission seats failed to pass, and the Board returned to its original five members.

Port

The needs of the Port of Coos Bay are underwent a study in 1991 to determine if a channel deepening was justified to meet current and future shipping needs. In 1991, the Port was instrumental in siting a nickel ore importing facility on the harbor, where shipments of nickel ore from New Caledonia will be received. In 1992, a copper·ore exporting terminal was under construction. The new import/export opportunities, combined with additional increases in shipping , volumes, provide the justification for a new harbor depth of 37 feet, with a: 45-foot entrance depth. In 1991-, the waterborne statistics for the Port of Coos Bay show 276 vessel calls, with a total outbound of 4,747,659 short tons, which represents an estimated value of $565,888,006. It has been conservatively estimated that the economic multiplier impact to the community is approximately $250,000 per vessel. Estimated direct community payrollfrom water transportation totaled approximately $18 million for the year.

Coos Bay Rail Line

In the early 1990s, prior to the acquisition of the Coos Bay line by RailTex, SP officials informed Oregon International Port of Coos Bay staff of deteriorating conditions on the Coos Bay rail bridge (a combination swing-span and trestle structure), and said that SP had no plans for rehabilitation or long-term maintenance of the bridge. Port staff immediately began working to acquire funds to improve the operating condition of the bridge and extend its service life. The Port was awarded $7.2 million in federal funds from the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21), and was then able to acquire a combination grant/loan from the State of Oregon as the non-federal cost share. In order to utilize public funds for Coos Bay rail bridge rehabilitation, the Port bought the bridge from Union Pacific for $1 in 2000.

Coos Bay Rail Line

Phase I rehabilitation was completed in May 2006, and Port staff then began planning for funding acquisition for Phase II work.

The Port’s continuing involvement in rail infrastructure development was the construction of the North Spit Rail Spur in 2004-05 for $4.4 million, providing freight rail access to hundreds of acres of industrially zoned property on the North Spit of lower Coos Bay. The 3.6 mile spur was completed in October 2005, and currently serves Southport Forest Products, which invested approximately $18 million in an energy-efficient, technologically advanced small log sawmill. Southport purchased 30 acres from the Port for development of the mill and the Port reinvested those funds in the rail spur project, with other funds coming from the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA), the State of Oregon and local funding sources. Southport has since added kiln-drying facilities, which have since been expanded.

Port Acquisition of the Coos Bay rail line

On September 21, 2007, rail service on the Coos Bay rail line was suspended by the CORP Railroad, which embargoed the line from Vaughn in Lane County to the North Spit of lower Coos Bay and filed for discontinuance of service on all connecting spurs. The embargo impacted Roseburg Forest Products, Georgia-Pacific, Southport Forest Products, American Bridge Manufacturing and several other rail shippers throughout the western Lane, western Douglas and Coos Counties region. CORP cited safety concerns in three tunnels on the line as the primary reason for the embargo, and later commented and confirmed that the line also had a backlog of deferred maintenance. The loss of freight rail service forced commodity shippers on the line to shift to trucking at much higher costs.

The Port, acting on behalf of southwest Oregon communities, and business operations served by the rail line, took action at the direction of the Port’s Board of Commissioners and moved ahead with acquisition of the rail line through a Feeder Line Application (FLA) action before the U.S. Surface Transportation Board. Financing of the acquisition was supported by a loan package administered by the Oregon Business Development Department. At the time the FLA was filed, CORP also sought abandonment of the Coos Bay line. Granting of abandonment action could have resulted in loss of the freight rail service and the rail corridor between Eugene and Coos County.

The Port bought the Coos Bay rail line in order to maintain freight rail service for existing industrial operations in the three-county southwest region and to maintain multimodal transportation access for marine terminals in the Coos Bay harbor. The Port is currently engaged in a variety of projects intended to diversify maritime commerce for the harbor. The acquisition of the CORP/RailAmerica portion of the line was funded through the conversion of grant awards from the SAFETEA:LU (Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users) federal program and a grant from the State of Oregon ConnectOregon I program. The conversion of the funding sources was approved by appropriate federal and state entities. The Port finalized the purchase of 111 miles of the CORP Coos Bay line from RailAmerica in March 2009.

Coos Bay Rail Line

Concurrent with the acquisition of the Coos Bay line, Port staff applied for federal stimulus funding available through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, and was successful in acquiring a $2.5 million grant, which was used for high-priority tunnel rehabilitation. That work was completed in fall 2010. Port staff continued pursuing additional federal and state funds for long-term rehabilitation of the rail line.

In August 2010, the Oregon Transportation Commission awarded the Port $7.8 million through the ConnectOregon III program for repairs to the rail line’s three swing-span bridges, upgrades for trestles and other bridges, and phase 3 and 4 tunnel repairs. The Port also was successful in obtaining a $13.5 million Tiger II (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery) grant in October 2010. These funds allow the Port to rehabilitate rail, ties, ballast and other track components to enable trains to travel at more efficient speeds. Additionally, the Port has used an estimated $1 million in grant funds from the Oregon Department of Transportation Rail Division (ODOT Rail) and the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) to pay for signal upgrades at several mainline at-grade crossings and to construct some new crossings to improve roadway and rail line crossing safety. This was followed by a grant award of $2.5 million from a SAFETEA:LU pilot program. These funds were used for the purchase of a more environmentally benign treated railroad tie for the rail line rehabilitation. The process is Chemonite® ACZA, and is used to replace creosote-treated rail ties.

In December 2010, the Port acquired the final 23.5 miles of track between Cordes on Coos Bay’s North Spit to Coquille, through an agreement with the Union Pacific Railroad. The Port went through an intense review process to identify a qualified and reputable short line railroad operator to manage train service and day-to-day maintenance on the Coos Bay line. The Port selected ARG Transportation Services, Inc. as the operator and has negotiated a management agreement with that firm. ARG negotiated a Cooperative Marketing Agreement (CMA) with UP, which includes provisions for interchange agreements with other connecting Oregon shortline railroads. The operating name for the rail line is Coos Bay Rail Link -- CBR. The Reporting Mark of CBR was assigned and approved by the American Association of Railroads (AAR) and rights to the reporting mark are held by the Port.

Cost-effective and competitive freight rail service on the Coos Bay rail line is essential for future diversification of the cargoes moving through the Coos Bay harbor and for support of existing and future industrial operations and corresponding job retention and creation in the south coast region. The Coos Bay line returned to service in early October 2011, with weekly train service between Eugene and the North Spit. Service south of the Coos Bay rail bridge to end-of-track at Coquille was restored in two phases; to the Coos Bay yard and south Coos Bay shippers in October 2012, and to end-of-track in April 2013. The line currently serves more than 12 customers in the three-county region.

Charleston Marina

Today, Charleston has become quite a popular tourism destination, serving as the gateway to a string of Oregon State Parks, the South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve (www.oregon.gov/dsl/ssnerr), established as the first national estuarine research reserve in 1974, and several ocean beaches. Sport fishing is now a year-round recreation opportunity in Charleston drawing visitors from across Oregon and the western U.S. Various community groups in Charleston celebrate seafood with a series of annual events; the Charleston Crab Feed in February, the Charleston Oyster Feed in April, the Charleston Seafood Festival in August, and OctoberFish. Other local events include the Oregon Shorebird Festival, a marine ecosystems lecture series at OIMB, and the Shore Acres Holiday Lights.

Port

The Port continues to promote sustainable development that enahnces the economy of the Southwest Oregon and the State. Port staff have worked diligently in the past few years to increase maritime and rail development. Major projects include the Channel Modfication project, marine terminal fesbility study, and capital improvement projects on Port owned and operated infrastructure in the Charleston Marina and Coos Bay Rail Line.

Coos Bay Rail Line

The Coos Bay Rail Line celebrated its 100 year anniversary in 2016 with a Railroad Centennial Event. In addition, Port staff have worked diligently to obtain grant funding for rehbilitation projects on the line, specifically on the nine tunnels and 38 bridges that are located on the line. The Tunnel Rehabilitation, Timber Bridge Rehabilitation and Bridge Rehabilitation project are currently underway at the Port of Coos Bay. On November 1, 2018, Port assumed operations of the Coos Bay Rail Line under the subsidiary Coos Bay Rail Linc Inc. making it both the owner and operator of the line.